- Home

- Simpson, Christopher; Miller, Mark Crispin;

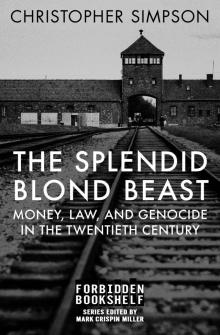

The Splendid Blond Beast

The Splendid Blond Beast Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ?

LOVE GREAT SALES?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS

DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

The Splendid Blond Beast

Money, Law, and Genocide in the Twentieth Century

Christopher Simpson

Contents

Series Introduction

1. The Splendid Blond Beast

2. “The Immediate Demands of Justice”

3. Young Turks

4. Bankers, Lawyers, and Linkage Groups

5. The Profits of Persecution

6. “Who Still Talks of the Armenians?”

7. No Action Required

8. Katyn

9. Silk Stocking Rebel

10. “The Present Ruling Class of Germany”

11. The Trials Begin

12. Morgenthau’s Plan

13. “This Needs to Be Dragged Out Into the Open”

14. Sunrise

15. White Lists

16. Prisoner Transfers

17. Double-Think on Denazification

18. “It Would Be Undesirable if This Became Publicly Known”

19. The End of the War Crimes Commission

20. Money, Law, and Genocide

Appendix

Notes and Sources

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Series Introduction

I

We the people seem to have the freest book trade in the world. Certainly we have the biggest. Cruise the mighty Amazon, and you will see so many books for sale in the United States today as would require more than four hundred miles of shelving to display them—a bookshelf that would stretch from Boston’s Old North Church to Fort McHenry in South Baltimore.

Surely that huge catalog is proof of our extraordinary freedom of expression: The US government does not ban books, because the First Amendment won’t allow it. While books are widely banned in states like China and Iran, no book may be forbidden by the US government at any level (although the CIA censors books by former officers). Where books are banned in the United States, the censors tend to be private organizations—church groups, school boards, and other local (busy) bodies roused to purify the public schools or libraries nearby.

Despite such local prohibitions, we can surely find any book we want. After all, it’s easy to locate those hot works that once were banned by the government as too “obscene” to sell, or mail, until the courts ruled otherwise on First Amendment grounds—Fanny Hill, Howl, Naked Lunch. We also have no trouble finding books banned here and there as “antifamily,” “Satanic,” “racist,” and/or “filthy,” from Huckleberry Finn to Heather Has Two Mommies to the Harry Potter series, just to name a few.

II

And yet, the fact that those bold books are all in print, and widely read, does not mean that we have the freest book trade in the world. On the contrary: For over half a century, America’s vast literary culture has been disparately policed, and imperceptibly contained, by state and corporate entities well placed and perfectly equipped to wipe out wayward writings. Their ad hoc suppressions through the years have been far more effectual than those quixotic bans imposed on classics like The Catcher in the Rye and Fahrenheit 451. For every one of those bestsellers scandalously purged from some provincial school curriculum, there are many others (we can’t know how many) that have been so thoroughly erased that few of us, if any, can remember them, or have ever heard of them.

How have all those books (to quote George Orwell) “dropped into the memory hole” in these United States? As America does not ban books, other means—less evident, and so less controversial—have been deployed to vaporize them. Some almost never made it into print, as publishers were privately warned off them from on high, either on the grounds of “national security” or with blunt threats of endless corporate litigation. Other books were signed enthusiastically—then “dumped,” as their own publishers mysteriously failed to market them, or even properly distribute them. But it has mainly been the press that stamps out inconvenient books, either by ignoring them, or—most often—laughing them off as “conspiracy theory,” despite their soundness (or because of it).

Once out of print, those books are gone. Even if some few of us have not forgotten them, and one might find used copies here and there, these books have disappeared. Missing from the shelves and never mentioned in the press (and seldom mentioned even in our schools), each book thus neutralized might just as well have been destroyed en masse—or never written in the first place, for all their contribution to the public good.

III

The purpose of this series is to bring such vanished books to life—first life for those that never saw the light of day, or barely did, and second life for those that got some notice, or even made a splash, then slipped too quickly out of print, and out of mind.

These books, by and large, were made to disappear, or were hastily forgotten, not because they were too lewd, heretical, or unpatriotic for some touchy group of citizens. These books sank without a trace, or faded fast, because they tell the sort of truths that Madison and Jefferson believed our Constitution should protect—truths that the people have the right to know, and needs to know, about our government and other powers that keep us in the dark.

Thus the works on our Forbidden Bookshelf shed new light—for most of us, it’s still new light—on the most troubling trends and episodes in US history, especially since World War II: America’s broad use of former Nazis and ex-Fascists in the Cold War; the Kennedy assassinations, and the murders of Martin Luther King Jr., Orlando Letelier, George Polk, and Paul Wellstone; Ronald Reagan’s Mafia connections, Richard Nixon’s close relationship with Jimmy Hoffa, and the mob’s grip on the NFL; America’s terroristic Phoenix Program in Vietnam, US support for South America’s most brutal tyrannies, and CIA involvement in the Middle East; the secret histories of DuPont, ITT, and other giant US corporations; and the long war waged by Wall Street and its allies in real estate on New York City’s poor and middle class.

The many vanished books on these forbidden subjects (among others) altogether constitute a shadow history of America—a history that We the People need to know at last, our country having now become a land with billionaires in charge, and millions not allowed to vote, and everybody under full surveillance. Through this series, we intend to pull that necessary history from the shadows at long last—to shed some light on how America got here, and how we might now take it somewhere else.

Mark Crispin Miller

There has always been a certain conflict between justice and the law.

HERBERT PELL

1

The Splendid Blond Beast

Friedrich Nietzsche called the aristocratic predators who write society’s laws “the splendid blond beast” precisely because they so often behave as though they are beyond the reach of elementary morality. As he saw things, these elites have cut a path toward a certain sort of excellence consisting mainly of the exercise of power at the expense of others. When dealing with ordinary people, he said, they “revert to the innocence of wild animals.… We can imagine them returning from an orgy of murder, arson, rape and torture, jubilant and at peace with themselves as though they had committed a fraternity prank—convinced, moreover, that the poets for a long time to come will have something to sing about and to praise.”1 Their brutality was true courage, Nietzsche thought, and the foundation of social order.

Today genocide—the deliberate destruction of a racial, cultural, or political group—is the paramount example of the instit

utionalized and sanctioned violence of which Nietzsche spoke. Genocide has been a basic mechanism of empire and the national state since their inception and remains widely practiced in “advanced” and “civilized” areas.2 Most genocides in this century have been perpetrated by nation-states upon ethnic minorities living within the state’s own borders; most of the victims have been children. The people responsible for mass murder have by and large gotten away with what they have done. Most have succeeded in keeping wealth that they looted from their victims; most have never faced trial. Genocide is still difficult to eradicate because it is usually tolerated, at least by those who benefit from it.

The Splendid Blond Beast examines how the social mechanisms of genocide often encourage tacit international cooperation in the escape from justice of those who perpetrated the crime. It looks at the social underpinnings and day-to-day dynamics of two mass crimes, the Armenian Genocide of 1915–18 and Hitler’s Holocaust of the Jews, as well as the U.S. government’s response to those tragedies.

According to psychologist Ervin Staub, who has studied dozens of mass crimes, genocidal societies usually go through an evolution during which the different strata of society literally learn how to carry out group murder. In his book The Roots of Evil, Staub contends that genocidal atrocities most often take place in countries under great political, economic, and often military stress. They are usually led by authoritarian parties that wield great power yet are insecure in their rule, such as the Nazis in Germany or the Ittihad (Committee of Union and Progress) in Turkey. The ideologies of such parties can vary in important respects, but they are nonetheless often similar in that they create unity among “in-group” members through dehumanization of outsiders. Genocidal societies also show a marked tendency toward what psychologists call “just-world” thinking: Victims are believed to have brought their suffering upon themselves and, thus, to deserve what they get.3

But the ideology of these authoritarian parties and even their seizure of state power are not necessarily enough to trigger a genocide. The leading perpetrators need mass mobilizations to actually implement their agenda. For example, the real spearheads of genocide in Germany—the Nazi party, SS, and similar groups—by themselves lacked the resources to disenfranchise and eventually murder millions of Jews. They succeeded in unleashing the Holocaust, however, by harnessing many of the otherwise ordinary elements of German life—of commerce, the courts, university scholarship, religious observance, routine government administration, and so on—to the specialized tasks necessary for mass murder. Not surprisingly, many of the leaders of these “ordinary” institutions were the existing notables in German society. The Nazi genocide probably would not have been possible without the active or tacit cooperation of many collaborators who did not consider themselves Nazis and, in some cases, even opposed aspects of Hitler’s policies, yet nonetheless cooperated in mass murder. Put bluntly, the Nazis succeeded in genocide in part through offering bystanders money, property, status, and other rewards for their active or tacit complicity in the crime.

The actions of Nazi Germany’s business elite illustrate how this works. Prior to 1933, German business leaders did not show a marked impulse toward genocide. Anti-Semitism was present in German commercial life, of course, but was often less pronounced there than in other European cultures of the day.4 Among the Nazis’ first acts in power, however, was the introduction of incentives to encourage persecution of Jews. New Aryanization laws created a profitable business for banks, corporations, and merchants willing to enforce Nazi racial preferences. Tens of thousands of Germans seized businesses or real estate owned by Jews, paying a fraction of the property’s true value, or drove Jewish competitors out of business.5 Jewish wealth, and later Jewish blood, provided an essential lubricant that kept Germany’s ruling coalition intact throughout its first decade in power. By 1944 and 1945, leaders of major German companies such as automaker Daimler Benz,6 electrical manufacturers AEG and Siemens,7 and most of Germany’s large mining, steelmaking, chemical, and construction companies found themselves deeply compromised by their exploitation of concentration camp labor, theft, and in some cases complicity in mass murder. They committed these crimes not so much out of ideological conviction but more often as a means of preserving their influence within Germany’s economy and society. For much of the German economic elite, their cooperation in atrocities was offered to Hitler’s government in exchange for its aid in maintaining their status.

A somewhat similar pattern of rewards for those who cooperate in persecution can be seen in other genocides. During the Turkish genocide of Armenians, the Ittihad government extended economic incentives to Turks willing to participate in the deportation and murder of Armenians.8 During the nineteenth century, the U.S. government offered bounties for murdering Native Americans and, perhaps more fundamentally, provided free farmland and other business opportunities to settlers willing to encroach on Native American territories.9 A similar process continues today, particularly in Central and South America.

Thus, in genocidal situations, mass violence can become entwined with the very institutions that give a society coherency. This has important implications for how perpetrators and their collaborators are treated once most of the killing is over. By the time the genocide has ended, it is usually clear that the ordinary, integrative institutions of society remained centers of power during the killing and shared responsibility for it.

These institutions usually hold on to some measure of authority in the wake of any economic or political crisis of legitimacy created by their actions. Even if the regime is brought down by a military defeat, as was the case in Turkey and in Nazi Germany, the residual power of these institutions means that there are likely to be factions among the victors, and even among the victims, who perceive an interest in allying themselves with the old power centers. Such cliques will conceal the old guard’s complicity in crime and exploit their relationship with the old power centers for political or economic advantage.

During the two genocides examined in this book, international law obstructed bystanders from rescuing victims of mass crimes and, in some cases, from punishing the perpetrators. The biases in international law that favored the powerful and prosperous also tended to protect and encourage persecutors, especially when these groups intertwined or overlapped. In fact, the social mechanisms of genocide—that is, how it works, how it is actually carried out—aborted the development of international laws and precedents that might otherwise have restricted genocides, particularly after World War I. Thus, the law and the crime became caught in a cycle in which the law facilitated the crime and the crime, in turn, helped institutionalize a form of law with which it could coexist. The losers in this vicious circle were the ordinary people, children, and rebels who have always borne the brunt of tyranny.

This symbiotic evolution of world order, on the one hand, and the destruction of innocent people, on the other, can be seen in the international treaties and legal precedents prior to World War II concerning war crimes and crimes against humanity. The body of war crimes law in effect during those years was written mainly by the United States and the major powers of Europe to favor themselves and to stigmatize rebellions by indigenous peoples or colonized countries. Understanding the complex and sometimes contradictory effects of these precedents is often difficult, however, because the very concept of war crime may seem paradoxical. The object and method of war would seem at first glance to be the destruction of other societies through murder, pillage, or any other means at hand. “War consists largely of acts that would be criminal if performed in time of peace—killing, wounding, kidnapping, destroying or carrying off other people’s property,” said Telford Taylor, the chief U.S. prosecutor at the second round of the Nuremberg trials. Often such conduct is not regarded as criminal if it takes place in the course of war, Taylor continued, “because the state of war lays a blanket of immunity over the warriors.”10

But under international treaties this immunity for warrio

rs is not absolute. Its boundaries are marked by what are known as the laws of war. The widely accepted Hague conventions on war crimes and the Geneva conventions on treatment of prisoners of war set limits on the conduct of commanders and soldiers during war, for example. Legally speaking, “enemy soldiers who surrender must not be killed, and are to be taken prisoner,” Taylor noted. “Captured cities and towns must not be pillaged, nor ‘undefended’ places bombarded; poisoned weapons and other arms ‘calculated to cause unnecessary suffering’ are forbidden.” Further, “When an army occupies enemy territory, it must endeavor to restore public order, and respect family honor and rights, the lives of persons, and private property, as well as religious convictions and practices.”

For most of this century, the protection of these treaties has extended almost exclusively to members of professional armies, fighting in uniform, with the authorization of their nation’s leaders. Insurgents who resisted official armies were only rarely protected by these treaties—in fact, they were often considered to have committed a war crime when they rebelled against prevailing authorities. Nazi leaders used that legal precedent to enlist German military support for the extraordinarily brutal antipartisan campaigns integral to the Holocaust.11 Allied forces meanwhile took advantage of a similar loophole to authorize bombing campaigns against German cities that even Franklin Roosevelt had condemned as a war crime as recently as 1939.12 Thus international law typically provided protection for the powerful and ruthless rather than for their victims.

The fact is that no clear international ban against crimes against humanity existed prior to 1945, due in large part to U.S. opposition. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity* are usually something a government does to its own people, such as genocide, slavery, or other forms of mass violence against civilians. Although such crimes were defined in detail at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg and in later United Nations action, even today they remain a relatively new concept in international law and often run counter to more established legal custom. Crimes against humanity remain considerably harder to prosecute than war crimes, narrowly defined, in part because criminal nation-states are unlikely to prosecute themselves, and because international diplomatic practice—particularly by the United States—has blocked the creation of an international criminal court that would have jurisdiction to try perpetrators of these atrocities. Even the most horrific cases of human rights abuses are often protected from international justice.

The Splendid Blond Beast

The Splendid Blond Beast